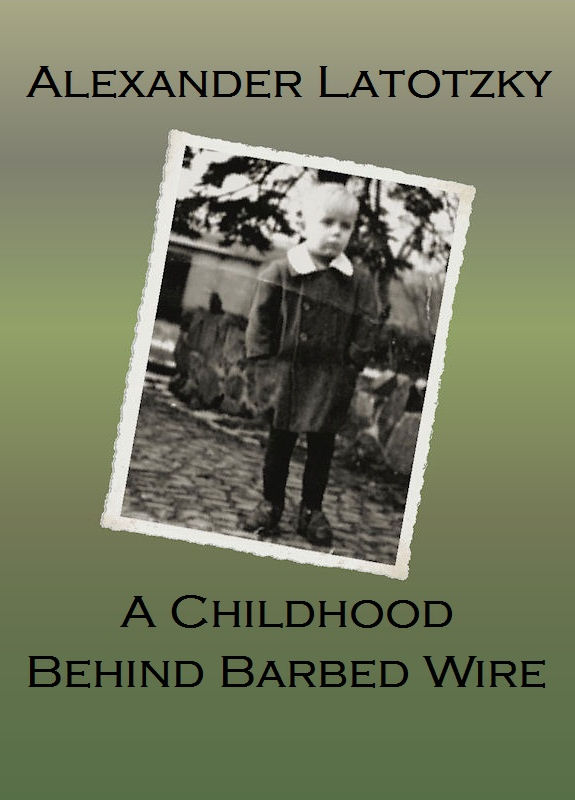

Everyone who grew up in East Germany (aka GDR) is familiar with the

novel "Naked Among Wolves" by Bruno Apitz who tells the story of

Jerzy Zweig, the "Child of Buchenwald". It was obligatory reading in

(the communist run) East German schools. But who in the GDR knew

that there were children living in Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen und the

other former concentration camps after WW II as well. Children, who

were born there, lived there - and sometimes even died there. They

were as innocent as Jerzy Zweig and all the other prisoners in the

Nazi concentration camps.

I am one of these children. I was born in 1948

in the Soviet special camp of Bautzen. At the age of only eight

weeks my mother and I were moved to the camp at Sachsenhausen where

I spent my first years until 1950 - together with many other

children. With the dissolution of the camps the women and children

were handed over to the East German authorities and sent to the

prison at Hoheneck. Here the children were separated from their

mothers for many years and, in some cases, forever.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall I have been

compiling a history of these events and was able to find more than

70 children with stories similar to mine. Not all of them survived

that time, but since 1998 I have been organizing annual reunions at

the former camps and prisons which today serve as memorials.

History can be best understood when one can

quote from real-life personal experiences. Therefore I will describe

a true case for condemnation and what could be better than my own

story.

After the war my mother lived with my

grandmother in Berlin. She was 19, almost 20 years old and survived

the hard times quite well. That is until early 1946. When she

returned to the flat one day in February 1946, she found my

grandmother dead. In the end, at her age of 58 she had not been able

to fend off two soviet men who had first raped then strangled her.

Both the culprits were still lying drunk and fast asleep in the

flat. My mother went to the police in good faith and reported the

murder, after all the war had been over for almost a year and law

and order had been re-established. Perhaps she also felt sure about

it, as she lived in the American Sector of Berlin. The State

Prosecutor took the case anyway and began to make enquiries.

Three weeks later, on March 25th, the

Headquarters of the Soviet Military Command in Berlin requested the

file, which since then has disappeared. At the State Prosecutor's

Office there is only a memo of the request and a note that the file

was never returned. Only five weeks later my mother was arrested by

Soviet soldiers in Senftenberg and sentenced to 15 years hard labour

by Soviet Military Tribunal on July 11th 1946 for alleged spying for

a foreign intelligence service.

In order to serve her sentence she was sent to

the special camp at Torgau. Here she got to know a young Ukrainian,

who was serving as a guard there. The guard came from the small town

of Grischki in the Ukraine, where he had been born in 1925 as the

youngest of five children. He started school at six, but had to

leave after two years to work on an a farm as a shepherd boy. At

this time in the Ukraine there was a wave of hunger of unbelievable

proportions due to Stalin's methods of forced collectivisation,

which claimed about 7 million lives. By making him work at this age

the parents could ensure that the boy survived. When the German Army

invaded the Soviet Union he was 15 years old and had direct and

close experiences of the horrors of war. In 1943, at the age of 18,

he was brought to Germany as forced labour. First of all he had to

work in the town of Brandenburg in a tank factory. In August 1943,

together with other forced labourers, he escaped from there, but was

recaptured on the German-Polish border and handed over to the

Gestapo. He was imprisoned in the Gestapo-prison in Schneidemühl and

thereafter in Deutschkrone, where he was set free at the end of the

war by the Red Army.

Following his release he was first threatened

with the fate of all Soviet forced labourers, as a traitor to the

fatherland he should be shot. By a lucky circumstance he managed to

avoid this fate. Just behind the front a new unit of stragglers from

the Red Army was being formed, so instead of being shot he was

pressed into the Army. However, first of all he had to go into a

military hospital, where he still was at the end of the war, then

after a short period of training was posted as Sergeant of the Guard

to the special camps of Buchenwald and later Torgau. Former

prisoners describe him as a shy and pleasant chap. Despite his

previous experiences this man fell in love with a prisoner at

Torgau, my mother. Although both of them must have known the risk

they were taking, a relationship developed between them. Whenever it

was possible, they met. Therefore, during his watch, he was always

leaving his post, which was then unmanned, whilst my mother was

always breaching the rules and regulations so that she might be put

into solitary confinement as a punishment.

All this came out at the trial before a

Military Tribunal of the Internal Troops on February 28th 1948, a

copy of which I managed to get hold of a few years ago, as

eventually their relationship resulted in my mother becoming

pregnant, of which the camp administration became aware. Someone

betrayed them however and my father was arrested and also imprisoned

in Torgau. Both of them underwent numerous interrogations but my

mother refused to name the father right to the end. However, he

confessed to the relationship in order to bring an end to the matter

and in the hope of a light sentence. For the crime of having sexual

relations with a German woman he was sentence to 6 years in the

Gulag and deported to Siberia. He left Torgau on 17 April 1948 with

900 other prisoners and was deported to a camp in Sukhobesvodnaye in

the USSR. He and my mother never saw each other again.

One day later I was born. A few days prior to

the birth my mother had been transferred to Bautzen, where I came

into the world. When I was 6 weeks old, we were send to

Sachsenhausen. We lived there in two barrack huts at the edge of the

camp in miserable conditions. One of three prisoners died,

regardless of whether they where old or young. It was left up to the

camp authorities to decide how to deal with the fact that there were

children present. We had no cloth, no nappies, no shoes or anything

else. One woman told me that we used clothes from people who died.

The mothers had to make do somehow and so it is no surprise to me

that not all of the children did survive.

In 1950 the special camps in the GDR were shut

down. But the nightmare story didn’t end for all mothers and

children. Nearly all the prisoners who belonged to the so-called

special contingent, amongst them 11 mothers with their children,

were released, but those who had been sentenced by Soviet Military

Tribunal were handed over to the DDR authorities to complete their

sentences. It was freezing cold when we left Sachsenhausen in

February 1950. Over 1.100 women and 30 children and babies were

taken, some by lorry, some on foot, to the railway station at

Oranienburg. They were transported in cattle trucks, with no heating

in the icy cold, lying on the bare straw, with insufficient food and

toilet facilities, to the town of Stollberg, from where they were

taken to Hoheneck prison located high above the town. For the women

it must have been a dreadful journey into an uncertain future. What

this journey really must have been like can be ascertained from the

final report of the People's Police. It does not just contain the

actual details about the exact number of persons handed over to the

GDR authorities, but there are also statements about the transport

arrangements. First of all we can find out from German sources

something about the existence of the children in the camps. „About

30" it says in the report by the People's Police regarding the

transport on 11 February 1950 and a further two women with suckling

children were checked in at Waldheim as being on the transport

before it was diverted to Hoheneck. No more was mentioned but all

the same there were many pregnant and heavily-pregnant women amongst

them. So it was that on 6 March, that is 4th weeks later, Johanna R.

gave birth to her son Gert in Hoheneck. Then on March 26th he was

followed by Viktor Harald and then on April 6th by the child of

Hildegard B. who died the same day. The child of Lieselotte H. also

died in the same year in Hoheneck. On April 12th a son was born to

Erika R., on June 4th Heinz-Rüdiger, on July 1st Dorothea, and so

on. The last one of those who had arrived from Sachsenhausen to give

birth was Elfriede L. on November 13th 1950. The child was

still-born and therefore not officially registered but a

hand-written note made on the prisoner's card kept in the prison.

When these women, alongside the approximately

30 babies or small children, who, in the space of a few days, had

arrived in Hoheneck from other camps, were admitted to the prison it

was completely overextended. Children had not been catered for in

prisons in the GDR, so the prison had a problem when it took over

those sentenced by Soviet Military Tribunal. They could not release

the mothers as the power of disposal of the women so sentenced lay

in the hands of the Soviets until 1954. They were unable to make a

ruling solely about the children, who had not been sentenced, but

were „appendages" to the women. A solution was sought and it was

probably Ellen Kuntz from the Land administration of the SED in

Saxony who found this solution. At least she was named in the

records of the People's Police as having been responsible for the

following: One day small buses drove up to the prison and then

several things happened: some women were told that the children had

to be examined by a doctor, or had to be photographed and whilst the

women were waiting in their cells, the children were led out of the

prison and loaded onto the buses. Later, the mothers themselves had

to put the children onto the buses; this was frequently done by

force. At this time the youngest child was just eight weeks old and

the eldest 3 years.

Without any sort of consideration mother and

child were torn apart and parted for years. All the women I

questioned found this a massively traumatic experience that only

healed years later, a long time after their release from prison.

These actions had been instigated by the then State Secretary for

Ministry of the Interior Hans Warnke, and carried out on February

28th 1950 via the Mother and Child prison governess and in the

ministry for Work and Health by Käthe Kern. For all the mothers,

including mine, the world fell apart.

The state of the women after they had been

parted from their children was described in a moving report by a

member of the Evangelical Church in 1953:

„Amongst the women who had been robbed of their

children was a Mrs. D. from Sachsenhausen. Her small daughter had

died in Sachsenhausen. Shortly afterwards her friend gave birth to a

child but died shortly after the birth. Frau D. took the small girl

to the nursery and looked after her lovingly. She had a small

picture of her own daughter, which someone had drawn for her on a

piece of paper. She was much attached to this picture and kept it

hidden away as drawings of this kind were forbidden in the camp.

After the child she had adopted had been taken away from her, the

guards also took the picture of her own daughter. Fran D. suffered a

nervous breakdown. The despairing cries of the woman could be heard

all day long even outside the prison."

I do not know how much the loss hurt my mother.

She did not say very much about it later. From the records of the

prison, which were made about her, it emerges, just how much she

missed me. Was she, as I can gather from the documents I have

managed to acquire in the meantime, in the beginning always full of

resistance to her tormentor, as can be seen from the punishment

book, of the prison, where all the talk is about rebelliousness

towards the guards, but this resistance was broken down more and

more with time. Added to that, as with all the prisoners, her health

slowly deteriorated, due to long years of under nourishment. In the

end her resistance was broken and, like all the others she went

around during the day in silence. As she stated in her personal

record written for the prison on her release: „After my release I

want to work in a mine or some other like occupation and thereby

ensure a secure future for my son..... [and] in doing so, also prove

that I am a full person." I think she was a full person her whole

life long.

The children were taken to a hospital in

Leipzig. The report of the then matron of the hospital lies in the

archives of the deacon of the Evangelic Church of Germany in Berlin.

She herself fled to the West in 1951, and in January 1953 wrote

about her experiences. So, in early 1950 she had received

instructions to install a children's ward in her hospital

immediately, and to expect 20-30 small children that very evening.

The hospital on Waldstrasse at that time had 350 beds. The hospital

did not cater for babies.

She succeeded in procuring the most necessary

items such as nappies, blankets, milk bottles and beds and made one

storey of the hospital into a children's wing. Late in the evening

the next day the first 10 children aged between 9 months and 3 years

arrived. The accompanying officer told her that the children did not

have any names and should be handled under the heading „Children of

the Land government”. She was forbidden to raise index cards about

them. Apart from that she was to ensure that no word of this was

made public.

On the following day the matron of the hospital

tried to acquire ration cards for the children. At first the ration

office refused to issue ration cards for children with no names. She

then managed to get some metal plates with a number for each child

from the People's Police, which were hung round the necks of the

older children and on the beds of the babies. Only then was the

ration office prepared to issue ration cards and later tickets for

shoes for the children, as none of them had proper shoes. They had

primitively-fashioned little shoes made from canvas. The name

“Sachsenhausen” had been sewn into the children's socks.

After a few days a further delivery of another

15 children arrived. The matron of the hospital seized the moment

when she was alone with the police doctor to ask urgently for the

names of the children. She realised that a child could die, and that

the manager of the cemetery would never accept a body without a

name. That made everything clear to the doctor, who placed the files

at her disposal for an hour. Humidly she wrote down the names at the

same time establishing the fact that the mothers were prisoners in

Hoheneck prison near Stollberg. The files also stated the crimes the

mothers had committed - illegal border crossing, spying, sabotage.

The mothers had all been previously imprisoned in Sachsenhausen.

Nearly every child had a bundle, in some cases

with adult things and frequently with a heartrending letter from

the mother, written on torn scraps of paper with a piece of plaster

or coal with details of the habits of the child as well as a request

to treat it kindly. There were also wishes for the child to be

handed over to certain relatives. Tips such as „Sascha has only ever

slept in my arms, be good to him,” or „Be nice to Dag, he has never

known a bed”, these and other such deeply moving requests were

frequent. The staff of the hospital tried to keep up with

everything, but at the beginning it was very difficult, because the

children were crying night and day for their mothers. It was also

difficult to calm the babies, as some of them had only just been

weaned. Five of the smallest children, whom the mothers could not

wean so quickly, without avoiding doing them harm, did not come on

the transport. They were later taken to children's home in Dresden.

Naturally the existence of the children could

not remain a secret and after a little while the grandmother of one

of the children turned up from Gera demanding the child be handed

over to her. The matron of the hospital had to refuse this request,

but reported it immediately to the Police President. Very soon

afterwards a second incident occurred. A father from Hamburg arrived

and demanded his child. He had been arrested with his pregnant wife

in 1946 and taken to Sachsenhausen. He had been released in January

1950, but his wife and boy had been taken to Stollberg in February

1950. At the hospital in Leipzig he went at once into the garden and

called his son. The little one ran to him immediately and they threw

their arms around one another. But he too had to leave the hospital

without his child, and was lucky, one could now say, to be pushed

back across the border to the West under guard by the People's

Police.

After these two incidents “the children of the

government” could no longer be concealed. The matron of the hospital

was now permitted to write letters to the relatives and very soon

thereafter 9 grandparents or other relatives arrived to take the

children away. The father from Hamburg sent a sister from the

evangelical mission to pick up his son. At the end there were 16

children left in Leipzig hospital, which the Police President

scornful said no-one wanted. Eventually, in November 1950 there were

transferred to three children's homes in Leipzig.

On the instructions of the Police President

each child was given a change-of-address and ration card with their

full names. The Waldstrasse hospital served as the last place of

residence and also the place of birth. The children were termed as

orphans. The whole exchange of letters with the authorities and the

relatives was handed over to the Police President. According to a

decision made by the Ministry of the Interior in 1952 these children

were to remain in the GDR.

The mothers in prison were told that their

children were now in a children's home, that they were well and that

the State would be responsible for their upbringing, by which an

upbringing in the socialist spirit was guaranteed. In some cases the

mothers were permitted to write to their children occasionally, but

any visit by relatives of the family living in freedom was

prohibited.

Now and again during their term of imprisonment

some mothers received photos of their child, which had probably been

taken by supervisors in the children's homes on the instructions of

the State. The women said they were only allowed to keep these

photos for a few hours to look at before they had to be handed back

and placed in their files.

From this point onwards all traces of the

children disappear, as, in the meantime, all documents concerning

them cannot be found. In none of the town-, district- or

state-archives, nor in the Federal archives, to whom I wrote, could

any documents concerning the homes be found. In response to a

request the mayor of Naunhof wrote to tell me that the files

concerning the children had been burnt in 1966/67. According to him,

this happened: ,As they were in unusable, mouldy condition". Much

the same happened with the documents for all the other children's

homes.

From 1954 the GDR received the right from the

Soviet Union to dispose of those sentenced by Soviet Military

Tribunal and they began to release them in installments. In July

1955 my mother's sentence was reduced to 10 years and on 31 March

1956 she was released to the Evangelical Church in Berlin-Teltow,

the only address that she could still give. From there, she went to

West Berlin and registered herself at the refugee camp in

Marienfelde where she met a man who had returned after having been a

prisoner of war in Russia for eleven years. They got married that

summer.

From

the very first day, my mother tried to fetch me to the West. She

wrote to the Red Cross, the German government, the East German

president, Wilhelm Pieck and I don’t know who else. But nobody

wanted to or was able to help her. Eventually she was directed by

the Central Organisation for Political Refugees from the East to

organisations in West Berlin; the Research Commission for

Independent Lawyers (UfJ) and the Struggle against Inhumanity (KgU)

led by Rainer Hildebrandt. There they planned my abduction. A

middleman was supposed to talk to me on my way to school in Seiffen

and then bring me to West Berlin. In order to prove that I was

really her child, she needed a birth certificate. But my mother

couldn’t produce one, as we only existed as an entry on our mothers’

prison record cards. I only got a birth certificate after I had

arrived in the West. This was only possible after several of the

former female prisoners confirmed that they had witnessed my birth

in Bautzen.

It was

only 45 years later that I found out from the Stasi (East German

secret police) files how my mother had managed to suddenly and

indeed legally fetch me to her in the West. In 1954 (I am not

exactly sure how long I was there) I was not in a home but staying

with a family. The daughter was a trainee at the children’s home and

her parents wanted to take me in. It is all just a fuzzy memory as

after all it was the first time that I was not in a camp, a prison

or a children’s home and I couldn’t get my head round it. But it was

only a short time. The prison leadership informed my mother that a

family wanted to take me in. She found out the name and address of

the family from a questionnaire that gave my current whereabouts.

She was very desperate and afraid that she was going to lose me

forever. The only a way out she saw was to work as a spy for the MfS

(Ministry of State Security)! She signed a contract and I went back

to the children’s home.

Just before her release in March 1956 she was

handed over to the “Soviet friends” with written permission from

Erich Mielke. Because she spoke Russian and was an interpreter, she

was given the job of spying on the Russian exiles organisation and

the Orthodox Church in West Berlin. But there was also a problem –

she was not trusted. Comrade Süß of the Ministry of State Security

wrote in his report “Without the existence of firm pledges, we

cannot consider her entirely trustworthy”. I am not sure who came up

with the solution, the KGB or the Ministry of State Security but my

mother was sent to the West and I had to stay in East Germany as a

“firm pledge”. A conversation with the head of my children’s home

took place in which she was given the instruction not to release me

to anyone without reference to an agreement of the Ministry of State

Security and to keep quiet about it.

As

already discussed, my mother secretly tried to get me out of East

Germany but without success. She did not know that the Ministry of

State Security knew about everything nor that the Stasi (state

police) had its eye on the Research Commission for Independent

Lawyers and other groups. In desperate letters to her commanding

officers First Lieutenant Hüttner and Second Lieutenant Süß, she

begged that I be allowed to come to her but without success.

It was

only in 1957 that the KGB and the Ministry for State Security were

convinced by her good work and at the age of almost 9 I was at last

allowed to go to her. But that was a mistake and shortly afterwards

all contact to her was stopped. As Colonel Trubnikow of the KGB

wrote, all her reports were made up and nothing she had done could

be turned into any concrete. But the “firm pledge”, me, had been

lost.

Since then

I have led a so called normal life.

We lived in a really quite

part of Berlin. Her husband adopted me a few years later and I took

the same surname as my mother. I remained the only child and as such

was spoilt. I studied, married and today have children and

grandchildren. Since 1990 I have worked as a historian and training

consultant. In the meantime in the course of my work I have found

more than 80 children, who were born in soviet special camps and

some of them meet their mothers now and again. We exchange

remembrances and try to help each other.

So, finally, there just remains the question of

what happened to a Russian sergeant, who had been sentenced to six

years in a prison camp in Siberia for his love of a German prisoner.

He survived the Gulag and was released into freedom after six years.

However, he had no money and therefore was unable to return to his

mother and sisters in his home town.

They

were still alive and he had not seen them since he had been

transported off to Germany in 1943. They had written to tell him

that his father and one of his sisters had starved to death during

the war. So he remained where he was and started work for the

railway. During the time he had spent in the camp he had got to know

a woman, whom he then married. Together they had four children.

He had not thought about a certain German

prisoner for a long time, nor about the child that he had never

seen. In all the years I too had never looked for him. I lived in

the belief that he was dead, as my mother had been told he had been

sentenced to death for his crime. It was 1997, when I received some

documents from Moscow by the German Red Cross, that I found this was

not true. I began to search for him and I was very lucky to find out

where he was living.

In 1999

I visited him for the first time in Russia. In 2000 he returned to

Germany on a visit for the first time after all the years, because

he wanted to see his grandchildren. It was not an easy visit for him

and he had hesitated a long time before making it.

After that all he only had one more wish: After

my grandmother had reached the incredible age of 102 he wants to

live one year longer so he can tell everyone this story.

His wish didn't come true; he died on Christmas

morning 2004 in the age of 79.

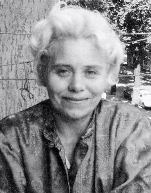

My Mother 1955

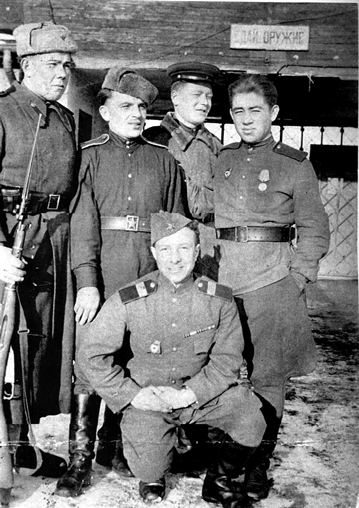

My Father 1943 in Germany

My Mother and Grandmother

Camp Buchenwald 1946

Kinderheim Naunhof 1951

The

Last Picture 1957

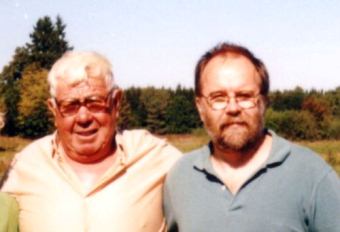

1999 in Russia

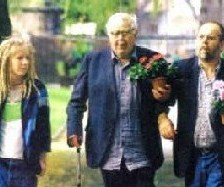

With My Daughter on the way to my mothers grave

2001 in Germany

as ebook here avalible